A country with one of the largest populations in the world is facing the worst of its political, social and economic challenges, ranging from political uncertainty to macroeconomic instability, security threats and social issues, rising poverty and unemployment, low growth and high inflation, with internal security issues emerging. It’s in an acute balance of payment (BOP) crisis with massive foreign debt repayments coming due while the kitty is almost empty.

Worse even, a war has erupted, disrupting global oil supplies and sending prices to historic highs, severely impacting the country’s already fragile external, monetary and fiscal finances even further. The political government in power is a coalition that is afraid any unpopular move would burn their political capital and their chances to stay in power would significantly diminish. The crisis took its course when the country saw unstable political setup before the government formed as a weak coalition. All of this has led to a loss of confidence in the country as a hub of business. This, along with a steep downgrading of country’s credit ratings by all credit rating agencies, led to foreign investors, expats, institutional investors, and others to pull their money out of the country.

Well, this is not the story of Pakistan, it’s India in 1990 through 1993.

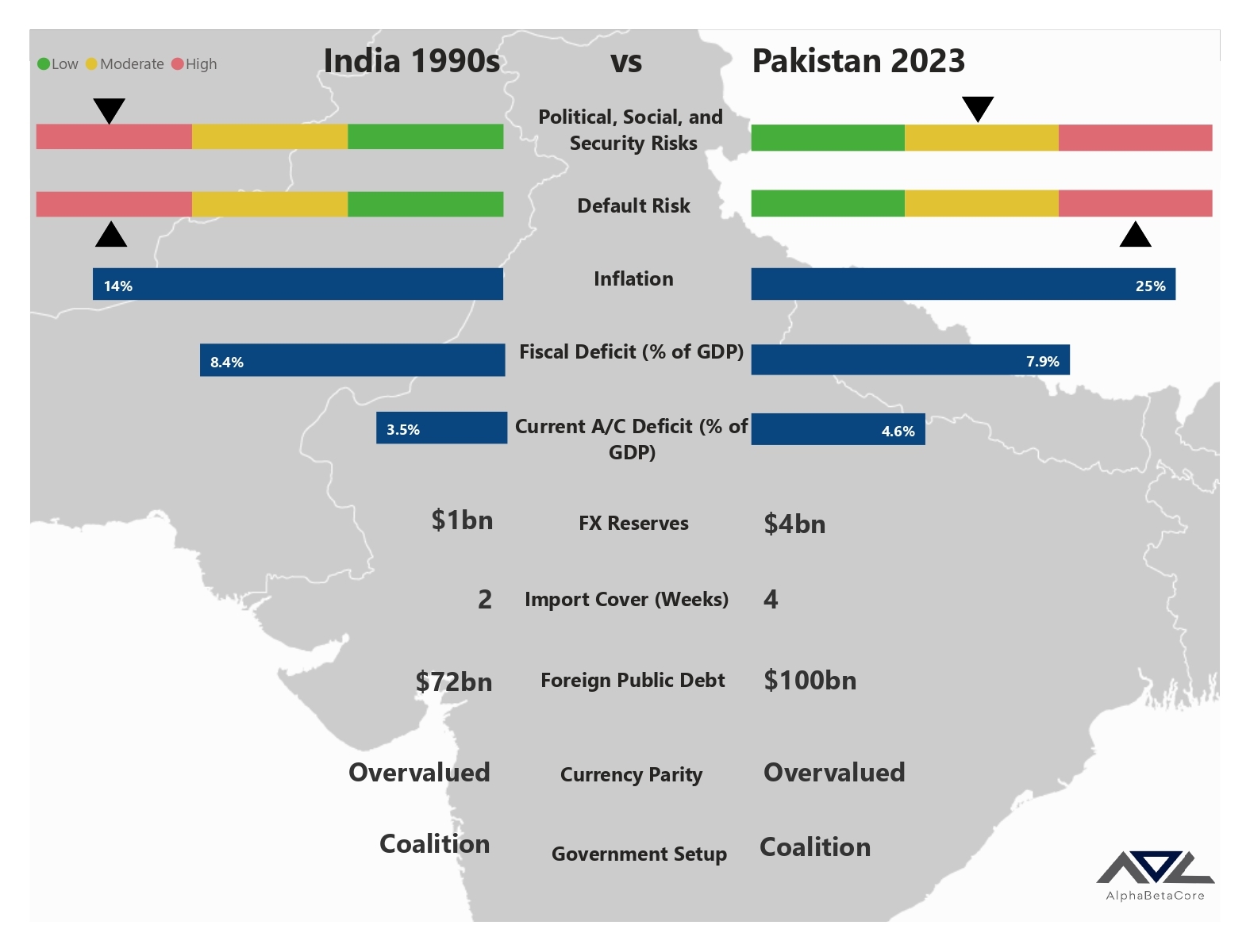

India in 1991 faced almost the same internal and external threats as Pakistan today. In fact, India faced far more severe internal security, religious, communal, political and therefore economic threats, than today’s Pakistan. For instance, in the early 1990s, India’s BOP was severely affected by the Gulf War, which sent Oil prices to new peaks (in a matter of 5 months, oil prices shot up from $15/bbl to $35/bbl, or a whopping 133%). Remittances to India fell due to the crisis hitting the Middle East, leading to extremely low forex reserves (two weeks of import cover) plunging the country into an acute BOP crisis, with fear of an economic collapse.

This was followed by a host of events, including Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in 1991, demolition of Babri Masjid in 1992, and Mumbai Serial blasts in 1993, leading to political turmoil, communal violence, security threats, and huge risks to country’s economy, which was already standing on fragile macros, entering into a deep crisis. Most of all, there was a hung parliament that was stuck more into political point-scoring than making some hard economic decisions the country direly needed for sustenance.

The political crisis took its course when India saw two PMs back-to-back in 1989 before 1991 government formed as a weak coalition. It lost all the confidence of the investors and businesses; all the more reasons to pull their money out of the country.

Similar is the case with Pakistan today, as the country plunges deep under the burden of several issues – both internal and external. Historic floods at home have inflicted an estimated $30 billion loss to the economy affecting 1/3rd of the land. A significant portion of agriculture and livestock was lost as a result (agriculture is 22% of GDP). Rising political instability led to macroeconomic challenges while internal security issues remerged. External factors including Russia-Ukraine war sent oil prices to historic high with spillover effects on food and energy markets, followed by global tightening to contain post-Covid inflation, plunging the world into recession.

Pakistan has 25% inflation, with full-year fiscal deficit recorded at 8% of GDP and current account deficit at 4.6% of GDP; now having reserves at $4.6bn (three-week import cover), and is experiencing extreme BOP crisis, followed by debt repayment capacity issues. Credit ratings have already been downgraded to speculative grades by all rating agencies with global bond prices reflecting high risk of default.

In 1991, India’s fiscal deficit was 8.4% of GDP, the BOP deficit was huge and the current account deficit was close to 3.5% of GDP with two-week import cover. Inflation also hovered high around 14% followed by low growth and rising unemployment. Currency was overvalued and India’s foreign reserves barely amounted to $1 billion while foreign debt was $72 billion (the 3rd-highest in the world back then).

India had to get into the IMF program for $1.8 billion with the conditions that the government would introduce necessary economic reforms in the budget. Not only did the government fail to introduce any reforms, it could not even present the budget due to its collapse in March 1991. The caretakers came into action and pledged 20 tons of gold with the Union Bank of Switzerland to raise $240 million to avert the crisis. Yet, the default risk still remained abound. India’s credit ratings were downgraded to speculative grade.

India’s dramatic comeback under Narsimha Rao

Pamulaparti Venkata Narasimha Rao – a socialist, weak PM (coalition government) with no political charisma or strong technical skills – was a true reformer with one strong attribute: Strong political will with skin in the game.

As they say, it takes only few good men to bring in change. Mr. Rao brought in an empowered team of a handful of men having credibility, trust and required competence, to make tough economic decisions. The team mainly included none other than Manmohan Singh (Finance Minister), P. Chidambaram (Minister of Commerce), Pranab Mukherjee (Deputy Chairperson, Planning Commission), and C. Rangarajan (Governor, Reserve Bank of India). They initiated economic liberalization with structural reforms, which laid the foundations of a modern India.

The key takeaway was, the PM continued to convince the coalition to stay put, while the finance minister and team went on to make decisions that were politically tough but economically beneficial to the long-term health of the Indian economy.

The first step the team took in India’s economic revival process was to devalue the overvalued Indian Rupee. It was two-step devaluation of currency (first step intended to test the market). The Indian Rupee was devalued by a whopping 23% against the greenback within a matter of three days (total devaluation of 59% in one year). At the same time, Mr. Chidambaram introduced a new export-oriented trade policy that defined India’s strategic trade objective with the world. Taxes were rather brought down while the country’s economy was opened up for foreign direct investments, by i) dismantling the chronic License Raj, ii) abolition of Monopolies & Restrictive Trade acts, and iii) privatization of state-owned entities. India improved trade relations with its neighbors, including China, by signing the South Asian Preferential Trade Agreement along with the SAARC countries.

The result from devaluation to trade and investment liberalization was, in three years, the non-oil trade deficit went into a surplus while growth took over with foreign investments flocking in. Obviously, Rao’s minority government faced extreme opposition in the face of tough economic reforms, but his political acumen kept both his own coalition and the opposition on a consensus while the reform went through. India’s budget for 1991 is hailed by many as one that laid the foundations of a modern India and the roadmap for pushing economic reforms in the country.

As opposed to common belief, where most still look for short-term solutions first to get the country out of the crisis, Pakistan’s economy needs hard reforms from day one. There are no short-cuts or immediate solutions to an economy that has been on IMF’s lap 23 times in the last 65 years with 13 times facing BOP crisis, and yet looks for a short-term recipe first to avoid the crisis, just to become complacent later.

Today, Pakistan is facing half of what India faced back in early 90s. But the approach and direction need to be that of a reformist than a typical political one, as the circumstances merit. Because, situations of economies may become similar in many ways at different points in time. However, what is important is, how the leaders and policymakers implement a calculated response to not only avert the crisis, but how to steer the country out of it and towards a long-term sustainable growth and prosperity path. This is what defines true leaders of nations.

Policy course for Pakistan

In Pakistan’s case, the reform strategy needs to be two-pronged and should be run in parallel: 1) mix of short-term administrative measures with policy response (BOP crisis, debt repayment, energy and fiscal consolidation), and 2) structural reforms (transformation for high sustainable growth).

Under the short-term strategy, there are four key areas to handle on priority: BOP crisis, debt repayments, energy management, and fiscal consolidation.

For context, every additional $1.0 billion now buys Pakistan economy four weeks, while foreign debt repayments between Jan 2023 and Dec 2023 are over $19.2 billion ($8 billion till June-23), so the country needs an average $1.6 billion every month for foreign debt repayment while to support growth at least at 3%, country’s Current Account Deficit is to be $500 million. In this regard, the country stands with slightly over $2 billion financing needs per month.

The short-term plan should to be based keeping this financing need in perspective. Further, most of the pledges/investments by multilaterals and bilaterals (announced during the Geneva Conference) are subject to a successful re-entry into the IMF program. So, the policymakers have to immediately do the following:

To contain BOP crisis, Pakistan needs to fulfill the IMF’s demands with a number of administrative and policy actions taken, as of yesterday, including the foremost decision of the exchange rate adjustment to market levels. Though majority adjustment in the currency parity has already taken place by the time this article is released, it will not be needed more than 20% in total to render the black market ineffective.

This will result in remittances and exports proceeds landing back into the formal channels, albeit gradually, thereby helping i) currency parity stabilize, ii) release import restrictions, iii) naturally contain import growth, and iv) improve export growth. This should be done on priority with commitment not to repeat the errors of unnecessarily tinkering with the exchange rate and intervening in the central bank’s autonomy with respect to monetary and external policy decisions.

Once the capital controls ease off, the currency parity needs to be kept little undervalued i.e., Real Effective Exchange Rates index remaining between 90-95 levels, so to keep an incentive for export while keeping imports in check. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) needs to shut down exchange companies, for the time being at least; only banks should deal in foreign currencies. This way, documentation will be ensured too besides better dollar-liquidity planning based on genuine import and payment needs.

Then there is a need for monetary tightening to contain core inflation (major part already done) to curtain money supply, which is double the regional average (28% of GDP in Pakistan compared to average 14% in India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka), followed by revising energy (gas) and petroleum product tariffs and taxes (to standard levels), reducing blanket subsidies, especially energy subsidies across the board, reducing energy transportation & distribution (T&D) losses by improving collection through strict compliance; all to significantly reduce external and fiscal burdens thereby containing deficits.

At the same time, on the fiscal side, three areas need immediate attention: 1) Tax Revenues, 2) Expenditures, and 3) Debt. First, there needs to be lower tax burden on the documented sector (remove super tax, special levies, turnover taxes and excessive duties, bring down sales tax by 2% to 15%, corporate tax rate to 25% – regional average), while broadening the tax base (tax burden on Industry is three times its share in GDP; Services sector half of their share in GDP, while Agriculture pays more than tax three times less than its share in GDP). The tax burden on the industry is over 26% of its value-added, while below 5% for both Services and Agriculture.

While redistributing the tax burden justifiably amongst the documented sectors while reducing the overall tax burden on them, there has to be a parallel effort to tax the untaxed (retail, real estate, tobacco, agriculture sectors, on their incomes), which could easily generate more than PKR 500 billion) to capture resource from these segments. As per the World Bank, Pakistan has substantial potential to increase tax receipts without imposing new taxes or raising tax rates. Further, if the compliance can be improved to 75%, Pakistan’s tax potential is 26% of GDP compared to below 10% of GDP on average for the last many years.

Non-filers, be it corporates or individuals, should only be allowed buying of basics; buying of any significant assets or conducting any transactions, including buying vehicles, real estate, traveling, hoteling, banking, business and trade should all be banned until the entity or the person becomes a filer. While a concerted effort be made for bringing the non-taxpayers into the net, filing process itself needs to be reformed for ease and simplicity for the masses. Finally, a taxpayer should be ensured of the reward and welfare for paying taxes instead of penalizing with more taxes and hassle, which has already discouraged the documented economy significantly so far.

Moreover, National Finance Commission Award (NFC) needs to be revisited where Provinces should be consulted for taking share of Debt and Defense for a fairer and more equitable share of the federal taxes and expenditures, besides a shared responsibility to generate revenues for self-sustenance. This should be devolved to the local governments for effective performance and timely service delivery to people at large.

On the expenditures side, the government needs to immediately cut public expenditure by at least

30% (across the board, cut federal affairs budget of PKR 500 billion into half; shut down most of the State-Owned Enterprises to save more than PKR 300 billion, initially), followed by planned restructuring of the SOEs for a full PKR 1 trillion savings per annum. There needs to be a planned reduction of subsidies (closing PKR 1.5 trillion) across the board to bring everything to market price levels, while protecting masses through targeted subsidies only.

Further, government ministries (many redundant after provincial autonomy) should be closed down. Size of the cabinet itself (nearly 80 ministers in various categories and capacities) need to be trimmed down to a level commensurate to federal operations and management. Ideally below 25 ministries. Next, the government employment across the board (federal as well as provincial) needs to be cut in half (close to 4.0 million now, to below 2.0 million) in a planned manner by way of offering various one-time incentives for smooth exits, especially to the lower-level cadres.

The collective salary and allowances bill of the federal and provincial employees (including civil and military) alone eats away over 38% into the Current Expenditures of the annual budget. Pension of about PKR 1 trillion is also another challenge in this regard, which needs to be adequately funded besides moratorium on both new appointments as well as growth in salaries and allowances until justified by performance and delivery. For efficient services delivery, the world is moving towards leaner and more effective governance models where there are fewer people and assets involved with more technology-driven delivery models at work. Next door UAE is a classic example of an efficient governance model.

On the debt repayment side, there has to be a comprehensive plan to reschedule both foreign and domestic debt, especially the portion falling due in the next three years. The rescheduling calls for at least five years of grace period, so any new government should be able to have sufficient time to plan and execute its economic strategy. There has to be a strict implementation of Fiscal Responsibility & Debt Limitation Act (FRDLA) with respect to government borrowing, especially from the domestic financial sector (FRDLA currently over 66% compared to 60% limit). Reduction in unproductive and wasteful expenditures, broadening of tax base with limiting borrowing can help achieve fiscal discipline.

On the energy management side, Pakistan needs to implement strict energy conservation policy, which includes work-from-home (WFH) policy across public and private sectors; closure of markets with strict implementation at 6:00pm for at least 6 months. The government needs to significantly cut on petrol allowances and use of excessive protocols using host of vehicles including fuel guzzlers, and instead use digital means for conducting all official affairs. The government should also reroute the remaining as well as the next-year’s budgeted PSDP (development funds) primarily towards energy to revamp the power sector’s T&D segment, which is the biggest cause for inefficiency in the energy sector, and therefore the biggest contributor to the circular debt issue (nearly PKR 4 trillion), chocking liquidity of the entire energy chain.

Diverting PSDP funds towards energy would be a critically-needed call by the policymakers, as 1) PSDP’s through-forward project pipeline has already ballooned with PKR 10 trillion of on-going or incomplete projects, and 2) energy chain is being dried up due to liquidity on account of rising circular debt issue. A switch of funds here for energy priority is inevitable.

Investment Strategy to unlock universe of growth potential

A comprehensive and focused investment strategy for attracting exports-driven foreign direct investment, encompassing ease of doing business ensuring delightful investor journey while restoring investor confidence through direction and clarity, needs to be built, keeping in view country’s potential of at least $10-15 billion annually. This is absolutely possible given Pakistan is i) a consumption story with a population play, ii) one of the youngest economies on earth, and iii) strategically located between resource-rich Middle-East and resource-hungry Asia Pacific, connecting almost half of world population.

The country offers an investment potential that ranges from entire petrochemical value-chain, to tourism & hospitality, food & agriculture, retail, construction, manufacturing & value-added, engineering & technology, energy & distribution, to IT services, just to name a few, alongside potential of developing a number of special economic zones and clusters that can feed both sides of the border.

As Churchill once said, “Never let a good crisis go to waste”. Essentially, a crisis is an opportunity. In this regard, government should be initiating a series of political, economic, civil, bureaucratic, security, legal, education, health and other structural reforms, which would set a fresh path to a sustainable growth journey, unlocking Pakistan’s potential. Political stability and policy consistency are two key ingredients for investors, which should be ensured at all costs, while accountability at the state, federal government and provincial levels should be for ‘not’ taking the decisions, rather than taking the decisions. This along with a key aspect of an effective governance model where responsibility resides with power needs to be ensured.

India’s 1990s case followed by hard reforms is a classic case study to look into and take lessons from. Manmohan Singh, in his first budget speech quoted Hugo Victor, “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come…”. What Pakistan can learn from the above game-plan by Rao and his men, for Pakistan, is that, a solid team based on competent, credible and empowered people, alongside a strong political will, can turnaround any tough economic situation.

Khurram Schehzad is an Investment Banker and Tech Entrepreneur by profession, a Development Economist by passion. Khurram has been advising Governments, Corporates, Financial Institutions, Startups and Investors on growth and transformations. His work experience spans more than 19 years across key financial disciplines, including Investment Banking, Corporate Finance, Investment Advisory & Strategy, Economic Policy & Research, and Asset & Portfolio Management.

Our elite n power corridors must bring their own dollars govt needs to slash down its expenses n cut its budget

Well written, however intentionally or unintentionally few things are overlooked, firstly military budget needs to be addressed too. There has to be an overhaul in the legal system as it stands it is corrupt as hell this lawlessness stops the foreign investments. Someone also needs to be brave enough to limit the mullahism and constant interference from religious groups into the economy, govt politics and life in general, we need to have a certain level of liberalism to attract the international companies, investors and masses of tourist to this beautiful country all this brings foreign currency which is badly needed.

Excellent analysis. However, three points are missing. We need to immediately open trade with India to get cheaper cotton and other raw materials. Second, we need to open up our economy through reduction of import tariffs as India did after 1991. Finally, we should stop new hardware defence procurements for the next 4-5 years. Also keeping one of the biggest standing armies with an economy like ours, will not work.

Pretty rich in content. Could have been better if customized solutions in the light of selected best practices in neighborhood countries be suggested for Pakistan.

Also a little more focus on expenditure could carve some pertinent suggestions.

Great effort, keep contributing.

What I’m interested in is to know why you thought it to be such a hot idea to lengthen the article by adding so much redundant info. I couldn’t even finish the damn thing and it made me sad.

Its not executable in Pakistan..

We have a different mindset where ppl believes that PAIT PAE PATHAR BAANDH LAIN GAY LAIKKIN JANG KI TAYYARI NAHI CHOHRAIN GAY KIU KAY ABHI AIK GHAZVA E HIND BHI HOUNA HAY…

Build some reading stamina instead of whining.

Very exhaustive and impressive analysis. In India, tough reforms were introduced and now the country is an economic giant. Let’s hope and pray that our policy makers finally decide to go for needed reforms and put the country back on track. Although it is herculean task but if there is will to fix the ailments to our economy there is no chance to fail at the end.

Nicely penned, very insightful

Excellent mate! Long but interesting read nevertheless. Haters to b ignored, u did such a great job by explaining the whole set of issues with a context n then giving out possible solutions in crisp n straight forward way.

Keep it up 👍🏼😇

Interesting article khurram sb, great work appreciated

Bravo excellent article l am not a professional in economic affairs but I sincerely believe that this can turn around the mess we are in right now and can steer the drifting ship into the right direction

Agreed.

Excellent analysis but lengthy.By the time one finishes the article it becomes difficult to retain the important points.Maybe a summary in kind of bullet points may have helped.Guess one will have to do that oneself.

Three fundamental factors need to be set right – first the feudal-military governance system that impedes any legislative and policy reforms and investment in human development, secondly a redundant judiciary and thirdly the perennial obsession with manipulation of religion. Given how, since three quarters of a century we have assiduously degenerated our ethos, it is very unlikely that we will even seek an initiative to set these on the correct course.

If he had presented such a paper before 10 Apr 2022, he’d have been offered SAPM Finance post immediately

A great read.

One of the key drivers of macroeconomic instability in the past two decades has been the international energy price shocks. Any reform package would include energy sector reforms aimed at relying on indegenoues energy sources (coal, hydel, and renewables), increasing the efficiency and financial sustainability of energy production and distribution systems.

We need to revamp our agricultural sector to reclaim comparative advantage in crops such as cotton, reduce our dependence on imported edible oil, and ensure food security.

Moreover, we missed the bus on IT revolution. Now we should do our best to not do the same with AI. The potential for talent development in AI must be fully realized.

Topnotches should sacrifice their overwhelmed perks and privileges

Great piece. Extremely intrigued at the India Pakistan comparison. Also a great idea to remind Pakistan of her insane numbers.

I wonder why you didn’t consider a) the bloated defence services, b) elite capture of land (both civilians and defence) c) land taxes, e) rentier economy. The challenge is to allow the Army to capture Pakistan….as its fief..no country in the world is in such shape..

The necessary precondition for any reform is that the political authority is THE single authority taking the calls. In Pakistan’s case this has never been true. Political will and interests of the establishment are not always congruent. This makes it far tougher for Pakistan to take charge of its course correction. I don’t see this changing in the near to mid term.